Tucked away on a quiet flag lot in Palo Alto, California, this 1966 mid-century home designed by Frank Lloyd Wright

protégé Aaron Green has been carefully extended and restored for a new generation. Originally built by Eichler Homes, the house remained virtually untouched for over five decades. Now, with a young family of five as its new custodians, the challenge was clear: how to double the home’s footprint without disturbing the clarity of Green’s original vision.

“We kept coming back to a single question,” say the architects behind the project, “What would Mr Green do today?” says the Schwartz and Architecture team.’

The answer was as much about restraint as it was about design. The team’s guiding principle became a line borrowed from Hippocrates: “First, do no harm.” While ironic—given the delays caused by the pandemic—the phrase came to shape every decision.

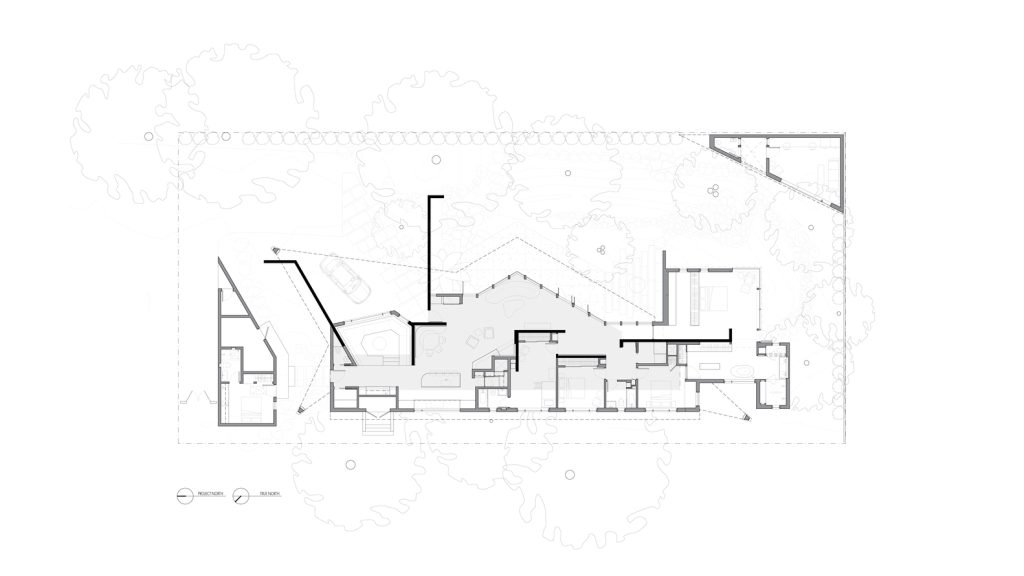

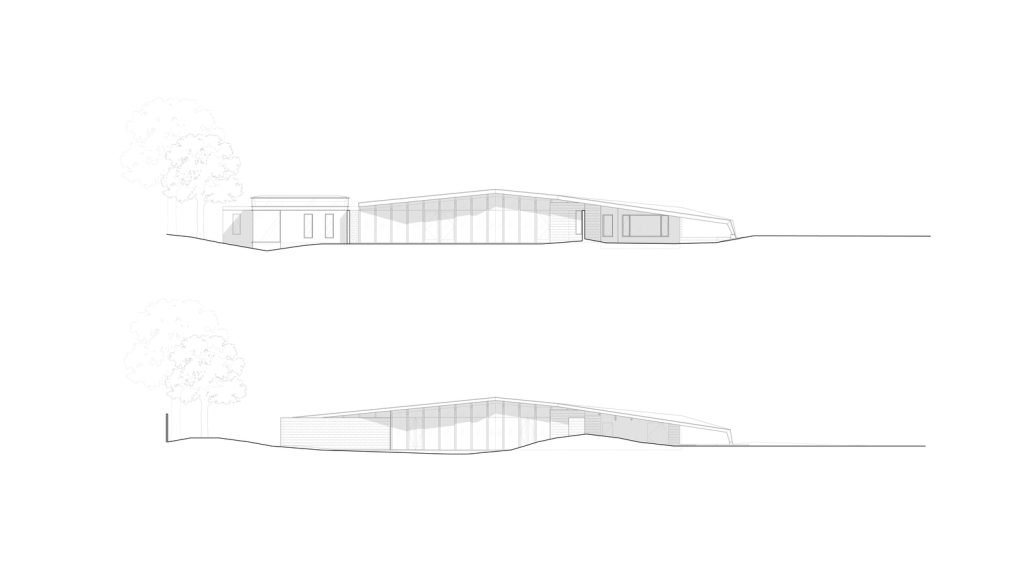

The original home measured 1,590 square feet, with three bedrooms and two bathrooms. Set on a third of an acre, the house sits behind more traditional suburban properties. It’s defined by its spider-like sculptural roof, a distinctive scupper system, and a carefully considered landscape that includes a swale running through the centre of the site. This subtle topography, key to managing the high water table, became a fixed point in the redesign.

The new brief called for space—lots of it. A prime bedroom suite, additional family areas, and an accessory dwelling unit had to be added without compromising the architectural integrity. The final footprint now stands at 3,102 square feet, but the additions are anything but obvious.

The first move was to intercept the original downward-sloping beams mid-span. This allowed the architects to build a full-length rear addition under a new upward-sloping roof. It brought light and height into what had been a dark kitchen and smaller bedrooms. The move respected the structural rhythm of the house while creating space for concealed lighting where the original beams once met.

“We weren’t interested in mimicry,” the architects explain. “Our additions are referential, not literal.”

At the front of the home, the existing carport was too low for modern vehicles and didn’t meet current building codes. The team raised the roofline and scupper, converting part of the area into a sunken family room. The gesture is subtle, but effective—blending mid-century proportions with new function.

A key design move was the creation of a new primary suite tucked behind a board-formed concrete wall. Drawing on the home’s original concrete block, the new wall is a quiet counterpoint—strong yet recessive. The addition’s clerestory windows add a touch of lightness, softening the weight of the original roofline and offering glimpses of the sculptural scuppers, which remain focal points from various interior views.

Throughout the process, the architects salvaged and integrated original built-in furniture, preserving the spirit of the home’s first chapter. And while the interior has been refreshed, the design language remains rooted in the mid-century ethos of simplicity, openness, and connection to nature.

“Our goal was to let the new interventions speak for themselves,” they say, “but always with Green’s legacy in mind.”

It’s a careful balance—modern yet timeless, expanded yet intact. And in answering their own question—what would Mr Green do?—they’ve found a solution that speaks fluently in both past and present tense.